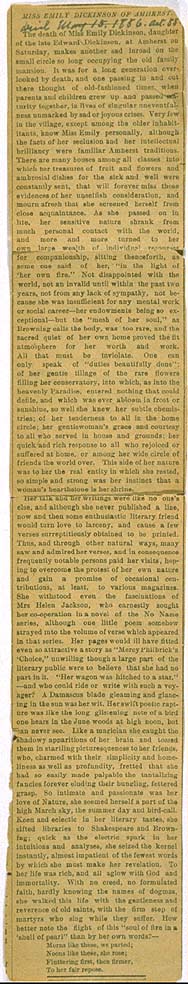

The death of Miss Emily Dickinson, daughter

of the late Edward Dickinson, at Amherst

on Saturday, makes another sad inroad on the

small circle so long occupying the old family

mansion. It was for a long generation over-

looked by death, and one passing in and out

there thought of old-fashioned times, when

parents and children grew up and passed ma-

turity together, in lives of singular uneventful-

ness unmarked by sad or joyous crises. Very few

in the village, excepting among the older inhabit-

itants, knew Miss Emily personally, although

the facts of her seclusion and her intellectual

brilliancy were familiar Amherst traditions.

There are many houses among all classes into

which her treasures of fruit and flowers and

ambrosial dishes for the sick and well were

constantly sent, that will forever miss those

evidences of her unselfish consideration, and

mourn afresh that she screened herself from

close acquaintance. As she passed on in

life, her sensitive nature shrank from

much personal contact with the world,

and more and more turned to her

own large wealth of individual resources

for companionship, sitting thenceforth, as

some one said of her, "In the light of

'her own fire." Not disappointed with the

world, not an invalid until within the past two

years, not from any lack of sympathy, not be-

cause she was insufficient of any mental work

or social career - her endowments being so ex-

ceptional - but the "mesh of her soul," as

Browning calls the body, was too rare, and the

sacred quiet of her own home proved the fit

atmosphere for her worth and work.

All that must be inviolate. One can

only speak of "duties beautifully done";

of her gentle tillage of the rare flowers

filling her conservatory, into which, as into the

heavenly Paradise, entered nothing that could

defile, and which was ever abloom in frost or

sunshine, so well she knew her subtle chemis-

tries; of her tenderness to all in the home

circle; her gentlewoman's grace and courtesy

to all who served in house and grounds; her

quick and rich response to all who rejoiced or

suffered at home, or among her wide circle of

friends the world over. This side of her nature

was to her the real entity in which she rested,

so simple and strong was her instinct that a

woman's hearthstone is her shrine.

Her talk and her writings were like no one's

else, and although she never published a line,

now and then some enthusiastic literary friend

would turn love to larceny, and cause a few

verses surreptitiously obtained to be printed.

Thus, and through other natural ways, many

saw and admired her verses, and in consequence

frequently notable presons paid her visits, hop-

ing to overcome the protest of her own nature

and gain a promise of occasional con-

tributions, at least, to various magazines.

She withstood even the fascinations of

mrs. Helen Jackson, who earnestly sought

her co-operation in a novel of the No-Name

series, although one little poem somehow

strayed into the volume of verse which appeared

in that series. Her pages would ill have fitted

even so attractive a story as "Mercy Philbrick's

Choice," unwilling though a large part of the

literary public were to believe that she had no

part in it. "Her wagon was hitched to a star,"

- and who could ride or write with such a voy-

ager? A Damascus blade gleaming and glanc-

ing in the sun was her wit. Her swift poetic rapt-

ure was like the long glistening note of a bird

one hears in the June woods at high noon, but

can never see. Like a magician she caught the

shadowy apparitions of her brain and tossed

them in startling picturesqueness to her friends,

who, charmed with their simplicity and home-

liness as well as profundity, fretted that she

had so easily made palpable the tantalizing

fancies forever eluding their bungling, fettered

grasp. So intimate and passionate a part of the

high march sky, the summer day and bird-call.

Keen and eclectic in her literary tastes, she

sifted libraries to Shakespeare and Brown-

ing; quick as the electric spark in her'

intuitions and analyses, she seized the kernel

instantly, almost impatient of the fewest words

by which she must make her revelation. To

her life was rich, and all aglow with God and

immortality. With no creed, no formulated

faith, hardly knowing the names of dogmas,

she walked this life with the gentleness and

reverence of old saints, with the firm step of

martyrs who sing while they suffer. How

better note the flight of this "soul of fire in a

shell of pearl" than by her own words? -

Morns like these, we parted;

Noons like these, she rose;

Fluttering first, then firmer,

To her fair repose.

La morte di Miss Emily Dickinson, figlia

del defunto Edward Dickinson, sabato

ad Amherst, è un altro triste momento nella

piccola cerchia vissuta così a lungo nella dimora

di questa antica famiglia. Essa fu a lungo rispar-

miata dalla morte, e a chi la frequentava

rammentava i vecchi tempi, quando

genitori e figli crescevano e invecchiavano

insieme, con una vita senza particolari scossoni

e non segnata da crisi di gioia e dolore. Molto pochi

in paese, salvo fra gli abitanti di più lunga data,

conoscevano Miss Emily personalmente, sebbene

la sua reclusione e la sua vivacità intellettuale

fossero ben conosciute ad Amherst.

Ci sono molte famiglie di tutte le classi sociali alle

quali i suoi tesori di frutta e fiori e

i suoi squisiti piatti per malati e sani erano

costantemente inviati, a cui mancheranno queste

prove della sua disinteressata considerazione,

insieme al rammarico per il suo rifuggire da

conoscenze più intime. Nel corso della sua

vita, la sua natura sensibile rifuggì da

gran parte dei contatti personali con il mondo,

e sempre di più si rivolse alla sua

grande ricchezza di risorse interiori

come compagnia, sedendo da allora, come

qualcuno disse di lei, "Nella luce del

suo stesso fuoco." Non delusa dal

mondo, non un'invalida se non negli ultimi due

anni, per nessuno aliena da comprensione, non

perché fosse inadeguata per il lavoro intellettuale

o la carriera sociale - essendo le sue doti così ec-

cezionali - ma "la maglia della sua anima", come

Browning chiama il corpo, era troppo rara, e la

sacra quiete della sua casa divenne la giusta

atmosfera per i suoi meriti e il suo lavoro.

Tutto ciò resti inviolato. Si può

solo parlare di "doveri meravigliosamente compiuti";

del suo coltivare con cura fiori rari

che riempivano la serra, nella quale, come nel

Paradiso celeste, non entrò nulla che potesse

corrompere, e che fu sempre in fiore nel gelo o nel

bel tempo, così bene conosceva le sue sottili alchi-

mie; della sua tenerezza per tutti nella cerchia

familiare; della sua grazia e cortesia da gentildonna per

tutti quelli che servivano in casa e nei campi; della sua

pronta e intensa risposta per tutti quelli che gioivano o

soffrivano in casa, o fra la sua ampia cerchia di

amici dappertutto. Questo lato della sua natura

era per lei l'entità concreta alla quale si poggiava,

così semplice e forte era il suo istinto che per una

donna il focolare è il suo altare.

Le sue parole e i suoi scritti non erano simili a nessun

altro, e benché non avesse mai pubblicato un rigo,

talvolta qualche entusiasta amico letterato

trasformò l'amore in ladrocinio, e fece sì che qualche

verso ottenuto di nascosto fosse pubblicato.

Così, e attraverso mezzi leciti, molti

videro e ammirarono i suoi versi, e di conseguenza

frequentemente persone illustri la interpellarono, spe-

rando di superare le rimostranze connaturate in lei

e ottenendo, al massimo, la promessa di un

occasionale contributo per varie riviste.

Resistette sempre al fascino di

mrs. Helen Jackson, che cercò assiduamente

la sua cooperazione per un romanzo di una collana

Anonima, anche se una breve poesia in qualche modo

si trovò ad apparire in un volume di versi

di quella collana. Le sue pagine furono maliziosamente

accostate a un sia pur avvincente romanzo come "Mercy

Philbrick's Choice", anche se larga parte del

pubblico letterario era restio a credere che avesse

a che fare con esso. "Il suo carro era attaccato a una stella",

- e chi potrebbe viaggiare o scrivere con un tale viag-

giatore? Una lama di Damasco che brilla e luccica

al sole era il suo ingegno. La fulminea estasi della sua

poesia era come la lunga nota scintillante di un uccello

che si sente a giugno nei boschi a mezzogiorno, ma che

nessuno riesce a vedere. Come un mago catturava

le misteriose apparizioni della sua mente e le lanciava

come sorprendenti chiazze di colore agli amici,

che, affascinati dalla sua semplicità e naturalez-

za ma anche dalla sua profondità, erano colpiti

da quella facilità nel rendere palpabili le allettanti

fantasie che sempre sfuggivano ai loro goffi tentativi di

afferrarle. Così vicina e intensa una parte dell'alta

marcia del cielo, i giorni d'estate e il canto degli uccelli.

Acuta ed eclettica nei suoi gusti letterari,

setacciava biblioteche da Shakespeare a Brown-

ing; veloce come una scintilla elettrica nelle sue

intuizioni e analisi, s'impadroniva del nocciolo

istantaneamente, quasi impaziente con le parole

che dovevano esternare quella rivelazione. Per

lei la vita era ricca, e tutta irraggiata da Dio e

dall'immortalità Non aveva un credo, nessuna fede

precostituita, a malapena conosceva i nomi dei dogmi,

percorse la vita con la leggerezza e la

reverenza degli antichi santi, con il passo fermo dei

martiri che cantano mentre soffrono. Quale

commento migliore al volo di questa "anima di fuoco in

un involucro di perla" che le sue stesse parole? -

In mattini come questi, ci separammo;

In meriggi come questi, lei s'innalzò;

Esitante dapprima, poi più sicura

Verso il suo giusto riposo.